Microfinance debt in Cambodia has resulted in “serious and systematic human rights abuses” and poses a “significant threat” to indebted families’ land holdings, according to a new report by two local rights groups.

- Story: Predatory Microlenders Abusing Rights of Poor Borrowers, Report Says

In “Collateral Damage: Land Loss and Abuses in Cambodia’s Microfinance Sector,” released today, rights group Licadho and housing rights NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) assail microfinance as “predatory” and riddled with unethical lending practices.

Drawing on 28 case studies of households that “suffered multiple and/or serious human rights abuses as a result of MFI debt,” the report claims the sector relies on coerced land sales, child labor, debt-driven migration and other abuses to thrive.

The allegations were rejected by MFIs, however, who said any such incidents were rare exceptions and pointed out the many policies and frameworks developed precisely to avoid such abuses on the whole. MFI leaders also described the exacting negotiations inherent to lender-borrower relationships.

Foreign shareholders, meanwhile, said they had confidence in the standards of their associated institutions in Cambodia and reserved judgment on the report’s findings.

At the start of this year, some 2.4 million Cambodians, about 15 percent of the population, held “at least $8 billion in outstanding micro loans,” including small loans from Acleda and Sathapana banks, the NGOs reported.

Using those figures, the average microloan debt per borrower was about $3,370, the highest average in the world, according to the NGO report. MFIs rejected the calculation as misrepresenting the debt of the average MFI client by lumping together loans intended for SMEs and low-income farmers.

From 2003 to 2014, loan sizes in Cambodia grew four times faster than borrowers’ incomes, according to a 2016 report from the Microfinance Index of Market Outreach and Saturation (MIMOSA) project.

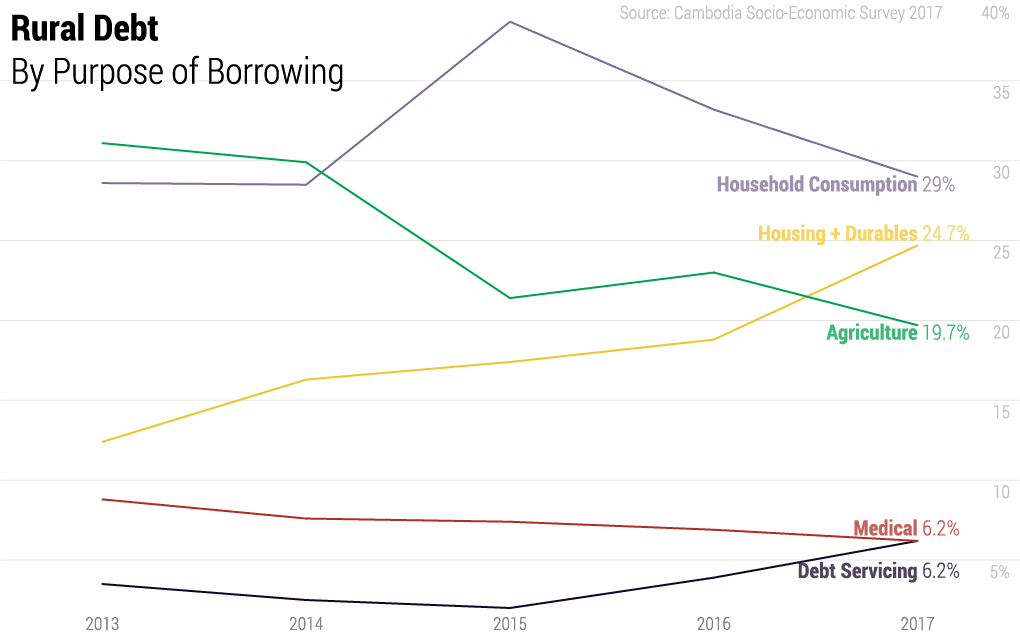

Nationwide “household consumption needs” topped the stated reasons for borrowing money each year from 2013 to 2017, with “agricultural activities” the second most common purpose, the government Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey said.

“Servicing and existing debts” and “illness, injury, accident” were the reasons for about 6 percent of outstanding loans each in 2017, according to the survey.

The seven largest MFIs — among more than 80 nationwide that are registered with the central bank — made combined profits of more than $130 million in 2017.

Coercing Land Sales

In 22 of the 28 documented cases featured in the report, loan officers threatened, ordered or pressured borrowers to sell their land — mostly income-generating property — to repay debts, the report says.

MFIs usually require borrowers’ land titles as collateral for all new loans, particularly those larger than $1,000, and all people interviewed by the organization said that they had provided a land title in exchange for a loan, according to Licadho and STT.

“Loss of land,” the report says, is “more than just a transfer of real estate: it jeopardizes a family’s livelihood, career and identity.”

An unpublished 2017 report on overindebtedness in Cambodia from the Warsaw-based Microfinance Centre and Sydney-based Good Return, which was seen by VOD, drew similar conclusions about the risks to land ownership.

Poor households face the “severe threat” of losing their means of livelihood by putting up their land as collateral, the 2017 report says. Yet it is the most commonly accepted form of collateral, it adds.

Formally, land repossession is a “very rare practice” — just one or two court cases per year for each bank or MFI, the report says.

Licadho and STT, however, say MFIs frequently pressure borrowers to sell their land rather than take it from them in court, skirting the law requiring financial institutions to “go through the courts when clients default.”

“The lack of extensive legal knowledge among MFI clients, low levels of financial literacy, and the very low levels of public trust in the highly corrupt Cambodian judiciary results in few clients ever exercising their right to a court-monitored default process,” according to the report.

In one case documented by the NGO report, Chamroeun (not his real name) took a $3,000 loan from LOLC to plant pepper and rubber trees. A year later, after his crops had failed but a payment was due, LOLC loan officers told Chamroeun to borrow from a private lender and introduced him to one, the report says.

MFI loans and informal private loans are used in tandem, forming a cycle that drives clients further into debt.

‘Collateral Damage’ report

While he initially resisted borrowing from the woman due to the high interest rate — common among private moneylenders offering fast, easy access to cash — “LOLC officers told him they would bring him to court if he did not pay, so he eventually agreed to take the private loan,” according to the report.

Struggling to pay back the private lender, Chamroeun later sold some land and took another loan from HKL, despite the fact that he had told the MFI that he would use the new loan to pay back the private lender. The HKL officers only required a land title from him, the NGOs said.

Again Chamroeun fell behind on payments, and resisted pressure from HKL to sell his land to a specific buyer, but eventually sold after the MFI sent 11 people to his house to threaten him with legal action, the report says.

“There are no benefits of MFIs,” Chamroeun told researchers. “I used to have food, but today my life is much more difficult.”

Unethical lending practices, including coercing land sales and referring borrowers to private lenders to assure repayment, are among the ways in which the sector maintains a low nonperforming loan ratio, reportedly 1.8 percent at the end of 2018, the report says.

The low percentage of loans with borrowers more than 30 days late on repayments was “made possible in-part because Cambodians are selling land, both productive farmland and homes, and borrowing additional money to repay their loans,” it says.

In addition, debt and pressure from loan officers, which is passed down from superiors, results in other rights abuses like debt bondage, child labor and other exploitative practices in the nation’s brick-making industry; labor migration, sometimes into risky work situations; and decreased food security, the report says.

Twenty households of 28 surveyed had “taken out at least one additional loan to repay an existing MFI loan, and 22 households had borrowed from a private lender while also borrowing from an MFI,” the NGOs reported.

The research, the groups said, suggests that “MFI loans and informal private loans are used in tandem, forming a cycle that drives clients further into debt.”

‘Bad Apples’

However, seven microfinance executives who gathered at Phnom Penh’s Cambodia Microfinance Association offices to speak to VOD on Monday extolled the many benefits of “access to finance” — the motorbikes, farm machinery, shops, houses and televisions sprouting up all around the countryside were emerging out of an economy oiled by microfinance, they said.

“For me, I love this microfinance very much because it helps the people,” said Bun Mony, an oknha who has been involved in microfinance for decades. He serves as CEO and director of Vithey Microfinance as well as vice chairman of the association.

Almost all of the day-to-day operations — 97 percent or more of clients — was smooth sailing, the executives said: Borrowers receive capital, and pay it back over time without needing to be chased down.

But the remainder could be a challenging business, they said.

Kea Borann, CEO of AMK and chairman of the association, said the margins sometimes contained “bad apples.”

The challenge for microfinance was “how we deal with 1 or 2 percent of cases,” he said.

“For every loan, we analyze ability to pay,” he said. But some loans inevitably led to failures and late payments.

In such cases, loan officers must determine whether clients’ troubles were genuine, and if they were, MFIs were open to negotiating a smaller payment, refinancing the debt or even writing off the loan, he said.

“We write off not less than $10 million a year,” Borann said, but added that the sector did not like to publicize the fact.

If all clients believed they could simply refuse to pay back their loans, the business would simply fall apart, he said.

“We write off loans every year but we can’t go out and tell people because it will lead to the collapse of the sector,” he said.

He added that, moreover, there were clients who refused to pay even when they had the ability.

“We have to take action because it will lead to thousands of bad apples,” he said, giving the example of a client recently claiming the total destruction of a mango farm due to wind damage.

“But when we go investigate, there’s minimal impact.”

We do our best to train our loan officers, but we can’t guarantee that loan officers will practice what they learn.

Dos Dinn, Amret CEO

For the most part, however, meeting repayment obligations came down to a matter of will on the part of borrowers, as Cambodian households typically had two to three income earners and multiple sources of revenue, he said.

“Most people who are willing to sort it out, they usually can sort it out,” he said.

“The cost of spending time chasing people to pay is far more expensive than lending. From an economic point of view, we don’t want that many people who can’t pay. We will spend more time dealing with problems than business.”

Dos Dinn, CEO of Amret and an association board member, said training, retraining and taking disciplinary action against errant loan officers was also part of the daily challenges of running a microfinance operation.

“We do our best to train our loan officers, but we can’t guarantee that loan officers will practice what they learn,” he said.

“The big question we need to answer: Is it systematically happening everywhere? Whether or not such practices are happening everywhere and threaten 50 percent of clients or not,” he added, questioning the NGO report’s sampling of only 28 households out of more than 2 million borrowers.

The sector was always honing its best practices, and needed hard data to see whether new guidelines were working, he said.

These included adhering to 95 indicators under the global Smart Campaign for client protection, following lending guidelines being developed by the association, and undertaking financial literacy education for the rural population, Dinn said.

“Sometimes the government [and the] public expect too much from microfinance because we’re working with the poor,” he added. “We can’t just expect everything from microfinance, and take a few examples and blame the whole industry. I sort of feel sometimes it’s unfair.”

AMK’s Borann added that the sector recognized there will always be some issues.

“But when we see a problem we take action,” he said. “Claiming everything is bad for the sector is too much. It’s a very one-sided approach.”

“There are a lot of positives in what we do. I don’t see anything in this world [that] has success without small negative impacts toward customers,” Borann said. “That is part of what we do. There’s a challenge we have to deal with. We’re aware of it. We’re working every day to understand and tackle those challenges.”

Reckoning With Recklessness

To address the sector’s problems, as it sees them, Licadho and STT recommended MFIs change their internal rules to prohibit requiring land titles as collateral for new loans, use the legal system in cases of default rather than pressuring borrowers to sell their land, and support independent investigations into industry practices while ensuring fair compensation to borrowers when wrongdoing is discovered.

The government should create or enforce laws and policies that promote ethical lending, such as preventing local authorities from pressuring borrowers to settle outstanding debts, and supporting the establishment of “pro-poor financing” and debt relief programs, and member-owned local financial institutions, the NGOs said.

MFI shareholders and lending partners should establish “regular and robust monitoring,” investigate abuses and support the reforms suggested to the government and the industry, the groups added.

Licadho director Naly Pilorge told VOD that the organization’s report was not just about “individual MFIs committing abuses.”

“It is about a sector that perpetuates abuses and relies on human rights abuses, at least in part, to sustain current levels of lending and repayment,” Pilorge said in an email.

“The sector as a whole needs to reckon with reckless lending and over-indebtedness, and needs to stop requiring land titles as collateral,” she said.

- Compagnie Financiere de la Bred, France

- Orix Corporation, Japan

- Sumitomo Mistui Banking Corporation, Japan

- Triodos Investment Management, NetherlandsAcleda Bank in Cambodia is one of our longstanding partners in the microfinance industry and known to us as an organisation that prides itself in having a high standard when it comes to responsible lending. As such, we do not recognise the image you say is being provided about Acleda Bank in the report. Nonetheless, we do take these kinds of signals very seriously and as such, we will address it with the organisation.

- Agora Microfinance, NetherlandsWe are confident that AMK’s practices have not caused any of the alleged problems, but will give it a thorough review nevertheless once we have access to the published report… Any human rights violations by our institutions will be unacceptable, and as mentioned, we have put in place standards to ensure it does not occur.

- Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank, Taiwan

- Advans, LuxembourgAdvans/Amret has not received the report from LICADHO which seems to have triggered your questions, or any information regarding the methodology used, and hence cannot comment neither on the content nor on the credibility of the results claimed in this report.

- Agence Francaise de Development, France*As we speak to you, AMRET stands out for its very good results in terms of the fight against over-indebtedness risk.

- CDC Group, U.K.*Microfinance is having positive social and financial impacts for households in Cambodia and has made it possible for borrowers to shift from informal to formal sources of credit, especially among the poor…if specific evidence of malpractice at Amret is presented to us then we will work with Advans to investigate and ensure that appropriate action is taken.

- European Investment Bank, E.U.*

- International Finance Corporation, World BankIFC works with microfinance institutions and stakeholders to incorporate responsible finance practices into all aspects of business operations, including training, capacity building, and risk management.

- KfW, Germany*From our insight, Amret is one of the few microfinance institutions in Cambodia that has fully implemented the Cambodian Microfinance Association…lending policy and reports monthly to its lenders on compliance. Amret is pursuing quality-oriented portfolio growth, which in 2018 increased significantly less compared to the overall market.

- Netherlands Development Finance, NetherlandsConsidering the number of Clients Amret is serving, breaches in policy on a few cases can be encountered. What matters to FMO is that clients then have all controls and processes in place to identify, report and limit the number of breaches.

- Bank of Ayudhya (Krungsri), Thailand

- PhillipCapital, Singapore

- Lanka Orix Leasing, Sri Lanka

- Lanka Orix Leasing, Sri Lanka

- Bank of East Asia, Hong Kong

- Maruhan Investment Asia, Japan

- Woori Bank, South Korea

Table updated on August 8 with comment from CDC Group.